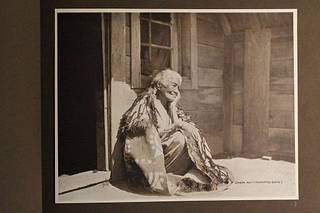

Maori elder. Portrait, 1891. (49bc05bd-fcb0-4c8c-8b1b-8e6222bcd99b)

Summary

Old Maori woman sits outside wooden house. Black and white photograph.

An elderly Maori sits on her heels in front of the doorway to a wooden house. She has short white hair and a faint tattoo around the mouth. She wears a stiff cloak, decorated with dangling cords, and a European-style dress with a plaid wool blanket wrapped around her. Full length portrait. Same woman in Item #8. From 'Maori studies' album with photographs taken by Thomas Pringle, collected by Charles Appleton Longfellow on his trip to New Zealand in 1891.

Archives Number: 1008-2-1-2-10-07

Keywords: charles appleton longfellow; maori; new zealand; thomas pringle; travel

The current consensus among archaeologists and anthropologists is that the Māori were the first people to settle in New Zealand. They arrived in the country from East Polynesia, and they brought with them their language, culture, and traditions. There is evidence that Māori cannibalism existed as early as the 14th century when the Māori first arrived in New Zealand. By the 17th century, however, there is evidence that cannibalism was a common practice among many Māori tribes. There are a number of reasons why Māori people practiced cannibalism. One reason was revenge. When a Māori warrior was killed in battle, his enemies might eat his flesh as a way of humiliating him and his tribe. Another reason for cannibalism was ritual. In some Māori tribes, it was believed that eating the flesh of an enemy would give the warrior the strength and courage of his opponent. Cannibalism was also sometimes practiced as a way of honoring the dead. In some tribes, it was believed that eating the flesh of a deceased relative would help them to pass into the afterlife. Finally, cannibalism was sometimes practiced out of necessity. In times of famine, Māori people might eat the flesh of their dead relatives in order to survive. Cannibalism was gradually outlawed by the Māori themselves in the early 19th century, and it was finally banned by the New Zealand government in 1842. However, there are some reports that isolated cases of cannibalism continued to occur until the late 19th century. The establishment of the first permanent European settlement in New Zealand occurred in 1840 with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi between the British Crown and Maori chiefs. The treaty recognized Maori sovereignty over their lands and guaranteed certain rights and protections. However, its implementation has been contentious, with significant breaches occurring over time. The subsequent waves of European settlers, known as Pakeha, brought British culture, technology, and systems of governance to New Zealand. This period also marked significant changes for the Maori population, as land disputes, conflicts, and cultural assimilation challenged their way of life. The Māori Wars were a series of conflicts fought between Māori and European settlers in New Zealand from 1845 to 1872. The wars were caused by a number of factors, including disputes over land ownership, the Treaty of Waitangi, and the growing influence of European culture. Māori Wars were fought in two main phases: the Musket Wars (1818-1830) and the Land Wars (1845-1872). The Musket Wars were a series of intertribal conflicts that were fought with muskets, which had been introduced to New Zealand by European traders. The Land Wars were fought between Māori and European settlers over the control of the land. The wars led to the decline of Māori power. The Māori were not definitively defeated by the British. They fought bravely and effectively, and they won some important battles. However, the British had a number of advantages, including superior weapons, technology, and numbers. Ultimately, the British were able to prevail, but at a great cost. It's important to recognize that European colonization had a profound impact on the Maori people, resulting in the loss of land, culture, and sovereignty. The effects of colonization are still felt today, and the Treaty of Waitangi remains a crucial document in New Zealand's legal and political landscape. While the settlement process has made progress in addressing some historical grievances, there are ongoing discussions about the need for further reparations and redress. Some argue that the current settlements are inadequate given the scale and depth of historical injustices and the ongoing disparities faced by Maori in areas such as health, education, and socio-economic outcomes. In recent decades, the New Zealand government has engaged in settlement processes with various Maori tribes to address historical grievances. These settlements typically involve financial and land-based compensation, cultural redress, and mechanisms for ongoing co-governance and partnership. The aim is to rectify past injustices and foster positive relationships between Maori and the government. During the period of British colonization in New Zealand, there were instances where British settlers appeared to adopt Maori customs or practices. The New Zealand Army has adopted the haka, a traditional Māori war dance, as its official ritual dance. The haka is characterized by rhythmic body movements, stomping feet, and tongue protrusion. The haka is often performed to challenge or intimidate opponents, but it can also be performed to welcome guests or to celebrate a victory. The first recorded instance of a British soldier performing the haka was in 1869, when Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, visited New Zealand. The Duke was greeted by a haka performed by a group of Māori warriors. The Duke was reportedly impressed by the haka, and he later ordered his own soldiers to learn the dance. In addition to the haka, the New Zealand Army also incorporates other Māori rituals into its ceremonies and traditions. These include the karakia, a Māori prayer, and the whaikōrero, a Māori speech. The use of Māori rituals in the New Zealand Army is a controversial issue.

Born in 1844, "Charley" Longfellow was the beloved first child of Henry and Fanny Longfellow. In 1863, he ran off to enlist as a private in the Union Army during the Civil War, and eventually received a commission as a lieutenant in a cavalry regiment. Miraculously, he survived a bout with malaria and what could have been a mortal wound in his back, which he received while on campaign in Virginia. After his wounding, he turned to sail. His 1866 voyage to England on his uncle's yacht the "Alice" set a record for a transatlantic crossing. From there he traveled on to Paris, and then to Russia and back. He accompanied brother Ernest to Europe on his honeymoon in 1868-1869 but soon lost interest in completing the Grand Tour and accepted an invitation to go to India where he stayed for 15 months, traveling around northern India and the Himalayas. He returned home via the newly opened Suez Canal. His Indian experiences are documented in some of the many photo albums he assembled. In 1871 Charley set off for Asia. He lived in Tokyo for almost two years. The furniture, works of art, porcelain, textiles, and books he sent back to 105 Brattle Street were early contributions to what became a "Japan Craze" in the United States. From Japan, Charley went to China and also managed to visit the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand before returning home in 1874. Between 1875 and 1891 he went to Cuba, Mexico, Scotland, Ireland, the Canary Islands, Madeira, Italy, North Africa, Turkey, France, the West Indies, Egypt, Scandinavia, Spain, Portugal, Wales, Colombia, Australia, and returned several times to England and Japan. Unlike other gentlemen travelers of his era, Charley wanted to experience life in his travel destinations, rather than merely observe it.

Tags

Date

Source

Copyright info