Similar

Letter, Ralph Waldo Emerson to Walt Whitman extolling Whitman's poetry, 21 July 1855

Summary

Reproduction number: A32 (color slide; page 1); A33 (color slide; pages 2 and 3); A34 (color slide; pages 4 and 5); LC-MSS-18630-5 (B&W negatives; pages 1-5)

Probably the most important letter in American literary history, both its generous writer and its grateful recipient were in the middle of their lives in 1855. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), however, was already established as the intellectual scion of the "Boston Brahmins"--descendants of the New England Puritan worthies of the seventeenth century--and had become the most respected essayist, philosopher, and lecturer of his generation. "Walter Whitman, Esq." (1819-1892), on the other hand, was a relatively unknown journalist and New York dandy who in 1855 burst upon the major literary scene with his anonymous first edition of Leaves of Grass.

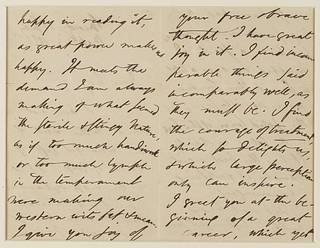

Though Whitman would spend the rest of his life revising and enlarging his compendium of poetry, Leaves of Grass first appeared as a simple, slim volume of untitled poems exhibiting a revolutionary style and content. Whitman's arresting, long free verse lines with irregular accents and his radically new celebration of the human body and of the common man were to shape the direction of American poetry for the next century. For the great Emerson to praise the self-published book of an unknown author as "the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed," was a coup of inestimable value to the younger poet. Whitman had carefully planted his name on the copyright page and identified himself within a verse on page twenty-nine, which enabled Emerson to contact him through the distributor, Fowler and Wells. With incredible foresight, Emerson greeted Whitman "at the beginning of a great career." He took "great joy" from Whitman's "free brave thought," in which he found "incomparable things said incomparably well."

Emerson's letter radically altered the critical diffidence, and Leaves of Grass quickly became a favorite among the cognoscenti, including leading abolitionists, though it never gained the favor of the masses in the poet's lifetime. Whitman, who was perhaps America's first self-publicist, allowed Emerson's letter to be published without the writer's permission in the New York Tribune and as a broadside. He then used parts of it on the cover of his next edition of Leaves of Grass, which in 1856 included new poems of a more erotic nature. Emerson was incensed, but Whitman was launched. He continued to publish major revisions of the book throughout his life--eleven different editions in all. As his opus developed through the Civil War years, it reflected major nineteenth-century events while continuing the celebration of self. With the last, big "Deathbed Edition" in 1892, Whitman's emphasis had shifted from the early erotic eclat to the heralding of poet as prophet and the celebration of a mystical democracy in lofty, philosophical tones.

This original Emerson letter, which perhaps saved America's greatest poet from oblivion, was the object of intense competition among major Whitman collectors--chiefly Charles E. Feinberg (1899-1988) and Oscar Lion. Feinberg obtained it from one of the heirs of Horace Traubel (1858-1919), a Whitman literary executor, and he eventually included it among the twenty thousand original items in the Charles E. Feinberg-Walt Whitman Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division. The Feinberg-Whitman Collection is the largest such collection of Whitman papers in existence.

Tags

Date

Source

Copyright info